Now it's time for the fifth post in the "Design Patterns" series. The last post was about the bridge pattern, but in this instalment I want to talk about the state pattern. This pattern is great when we have many state flags and want to perform an action based on the configuration of the flags. The actions are usually protected by a wall of ifs. The state pattern helps us get rid of the flags and of ifs by replacing them with a much more civilised set of classes. And who does not love classes?

The code presented in this post can be found at: https://github.com/Nivo1985/net_patterns. Please note that the projects in the solution match the names of the patterns.

What is our goal?

We want to create an application. I know, this is a shocker. The idea is quite simple. The application should allow us to perform a number of basic operations on an order. The operations include actions such as: create a new order, submit the order, cancel the order, and inform the system that the order date has expired.

What is the old way?

This is a typical problem of the state. Why actually? Good question. Mainly because we can try to name the states of the order and they will come up by themselves. For example, if the order is in the "New" state, it means that it has been created but is not yet being processed. Let us try one more time. The order is in the Cancelled status. This means that it was cancelled at some point in its lifetime. See? That comes naturally.

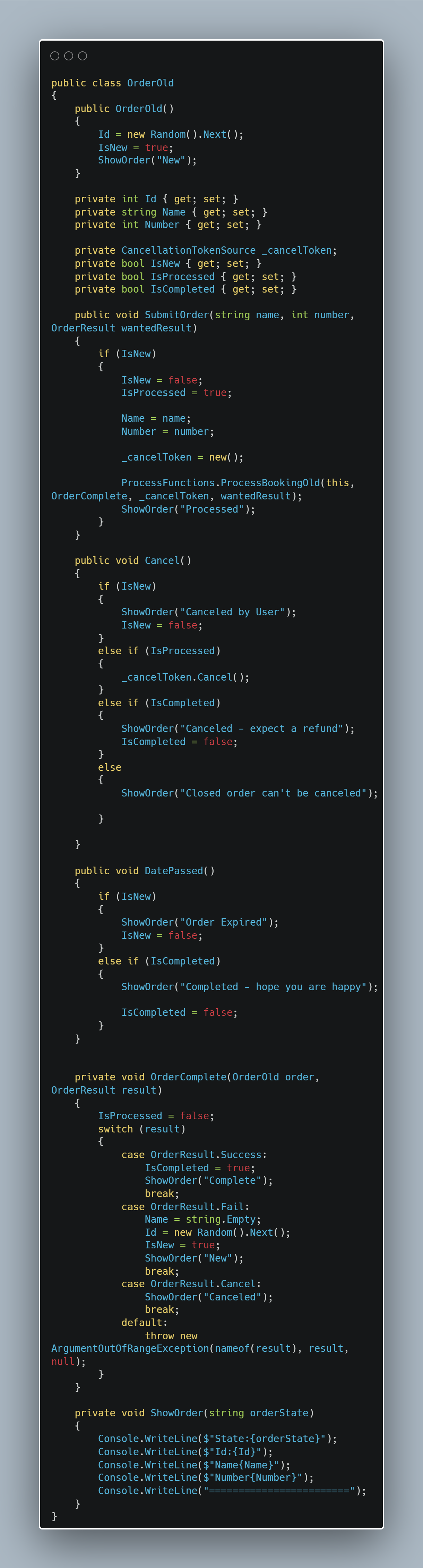

Now let us look at an old code that supports such a solution. The code is shown below.

I must be honest. I have committed such a code more than once. The code where most inner logic is based on a bool/enum fields and some kind of if based nightmare to find some logic in all of that. In the example above there are three flags: IsNew, IsProcessed and IsCompleted. Their names are quite straightforward. They tell us if the order is new, did a processing began and was the order completed. Respectively.

The second part of a problem / solution are the ifs. In this approach, they are the only way to determine what needs to be done. For what needs to be done is determined by the state of the order.

Ok. So, what is wrong with this code? As I said, I have created such a code more than once. The first problem is that it is a big pile of…. Code. That’s why the readability of the code is atrocious. It is hard to tell what is going on with the object and what state we are currently in.

The second issue is the extensibility of the code. Let’s say I want to change something in the new state. I don’t have a go-to place to do that. I would have to go through all the process method to do it. The more states that come up, the more problems there are with this approach.

There has to be a better way, and there is. Let us see what State Pattern can do for us.

Discover the new way

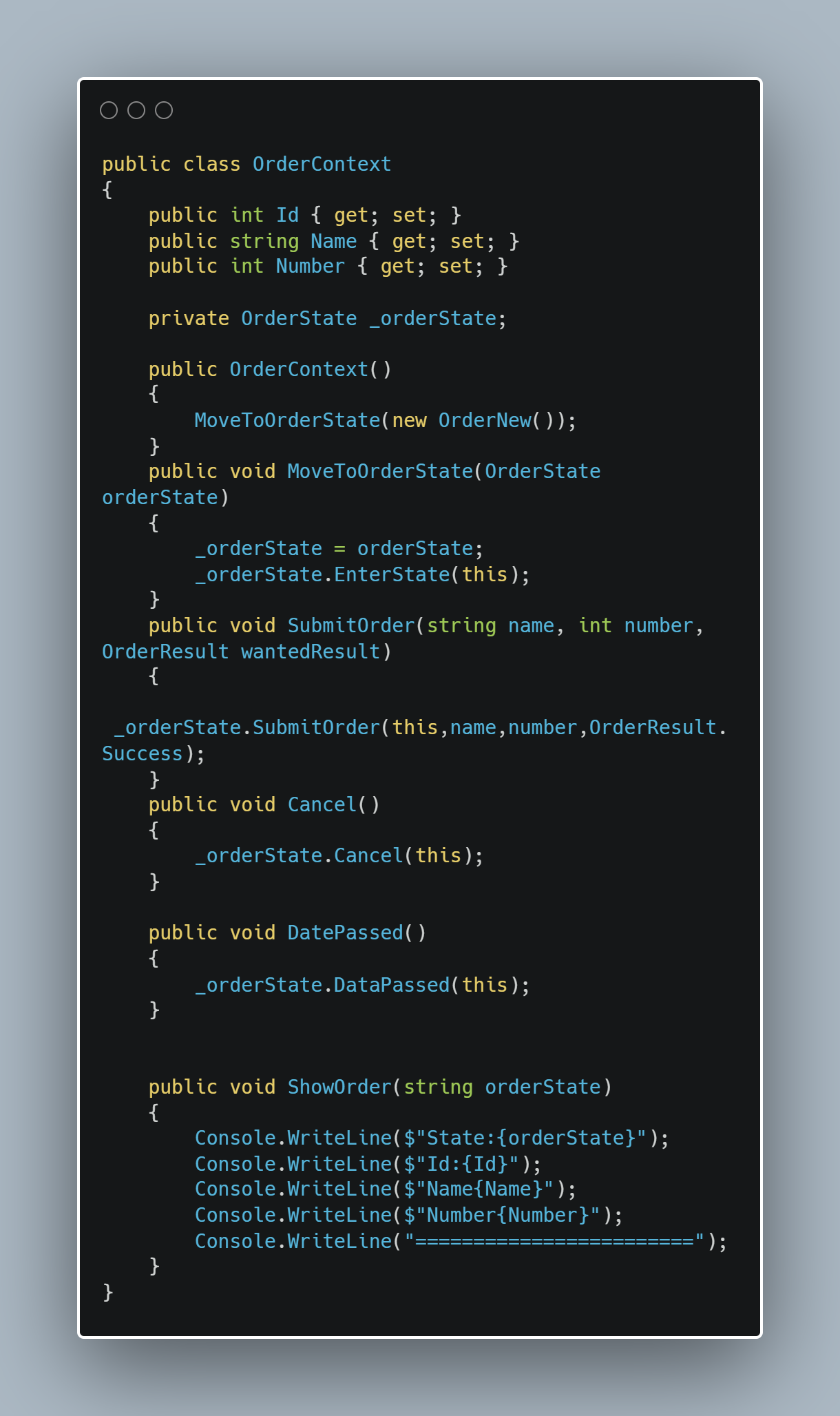

Before we begin, I have to give a heads up. The code is going to be a little more complex. But in doing so, we will gain readability and extensibility. The idea is to skip ifs and use objects in concrete state. The state itself would have the knowledge of what to do for each action. But before that, we need to add another element, the context. It will be like an engine object that works with the states and provides a kind of utility level.

We can see three familiar elements: SubmitOrder, Cancel, and DatPassed. They correspond to the method we have already seen and are the actions that the order object can perform. As we can see, all they do is call a method from the state object.

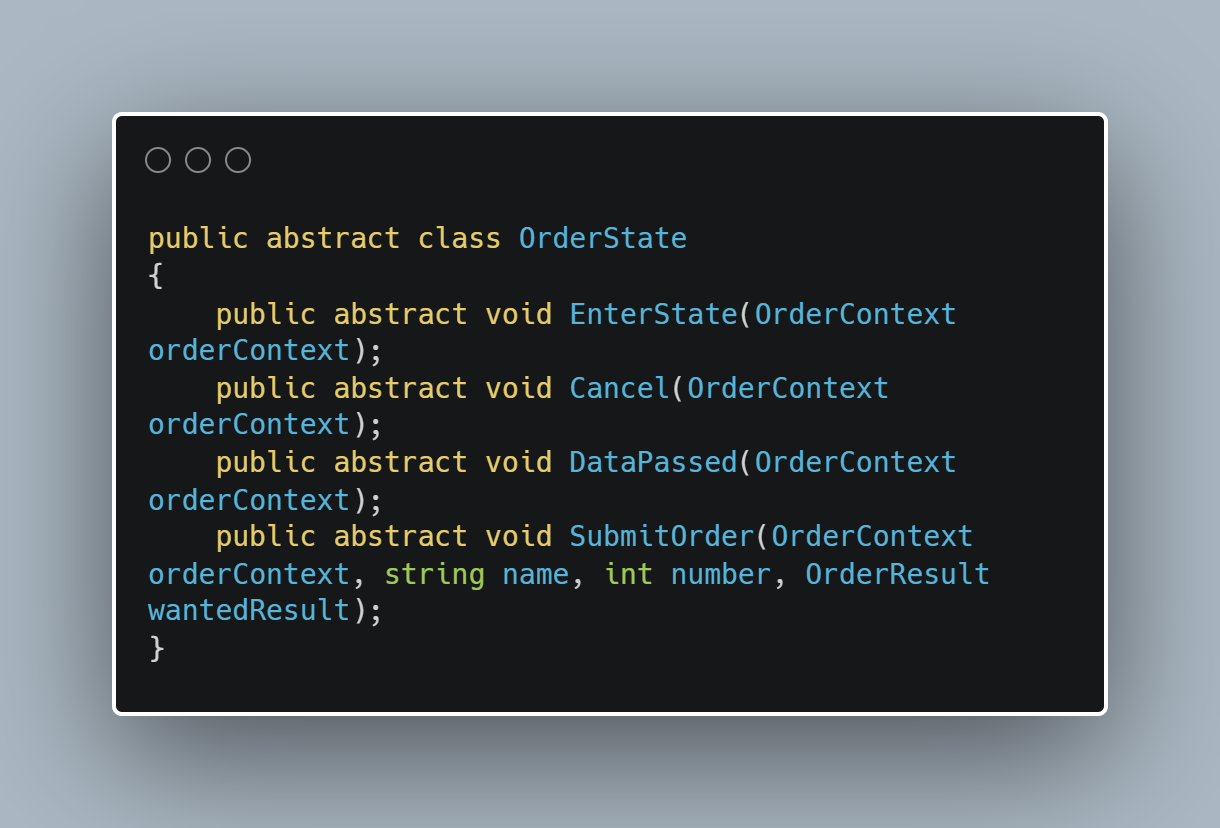

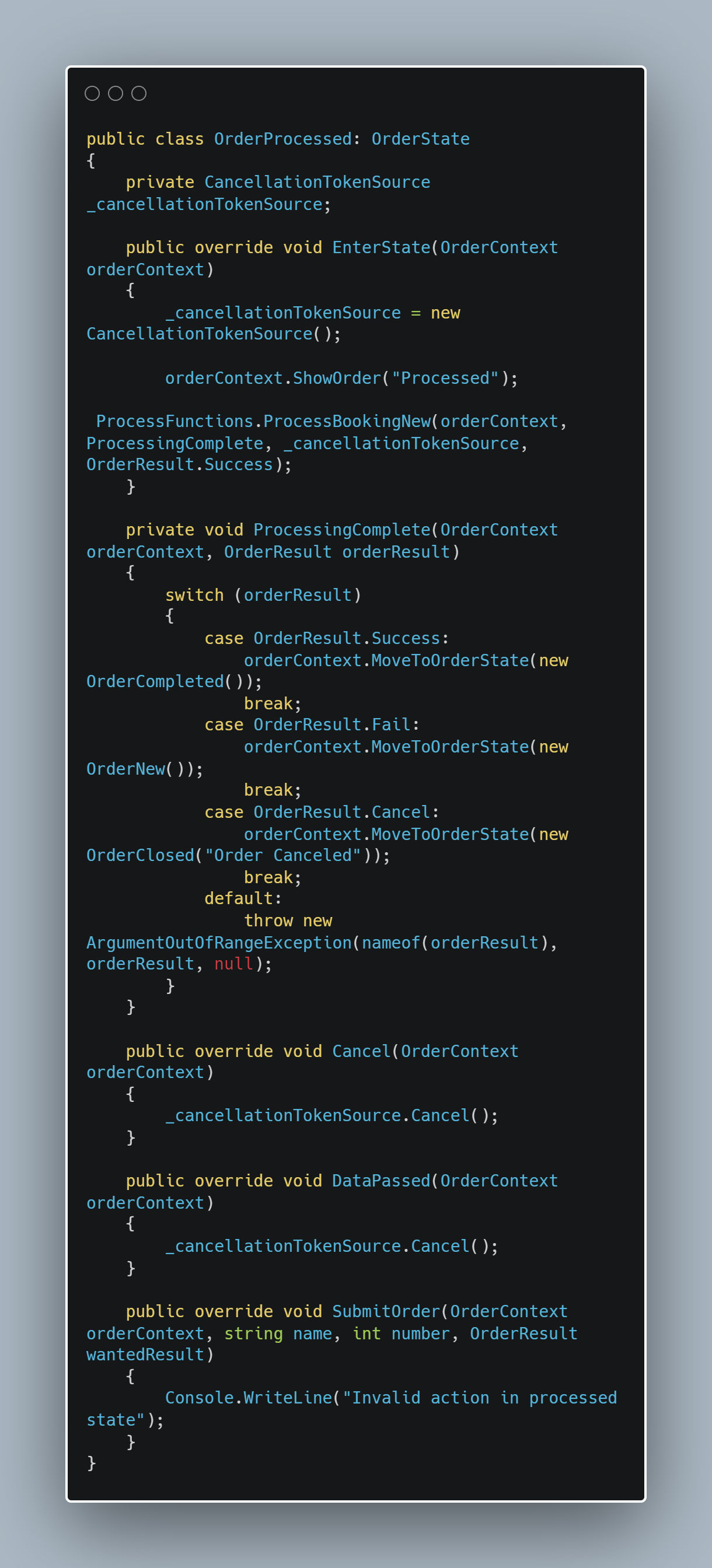

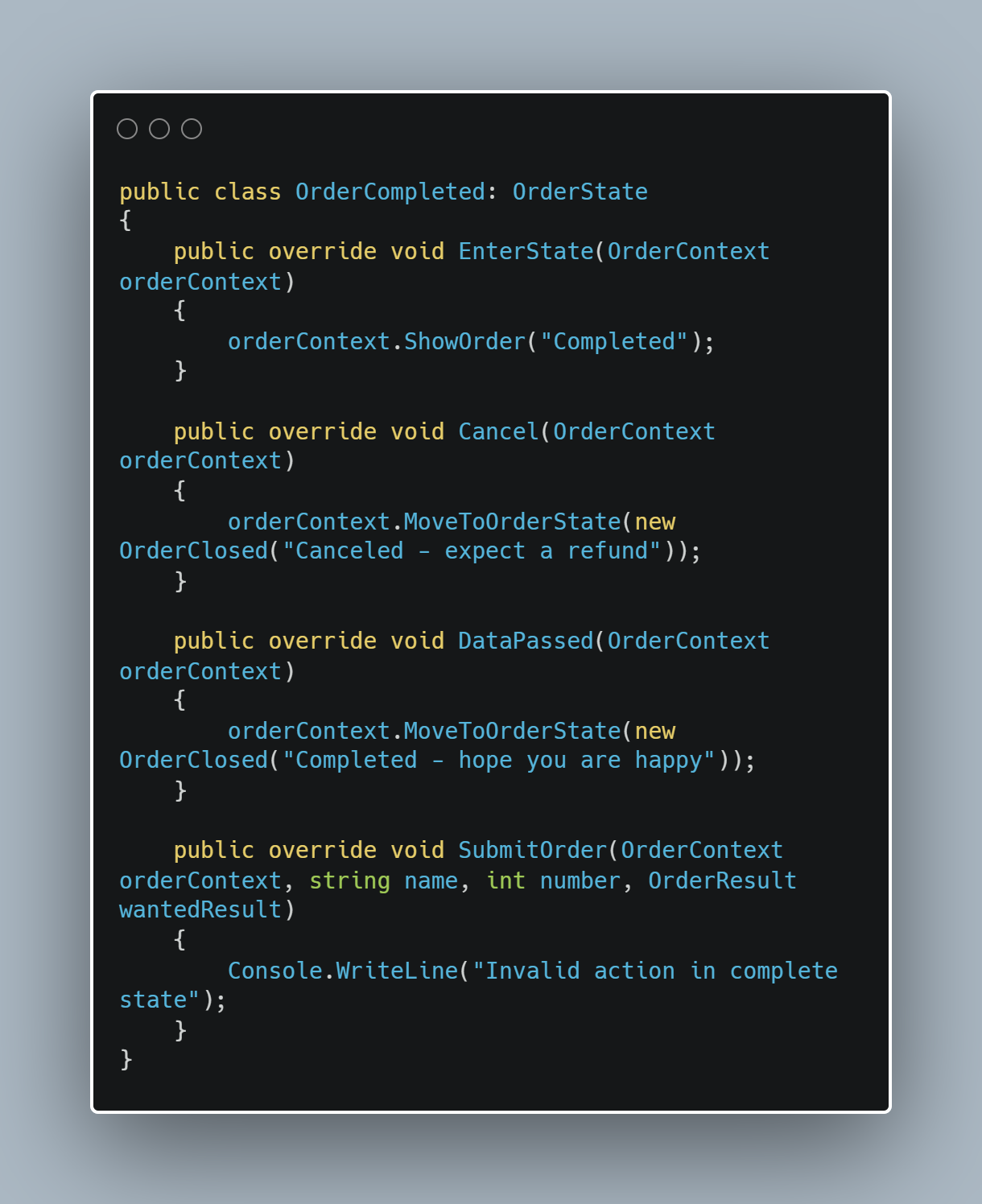

The state pattern mechanism is hidden in MoveToOrderState. This method sets the _ordeState field to the new state. The state is just a simple object that is aware of itself and knows what to do in each situation. In our application there are four states: New, Closed, Processed, and Completed. Each class that represents them derives from a base abstract state class.

The class has all the methods that our end classes are going to implement. And that’s it, nothing special really. The classes will be something special, mainly because they are so simple.

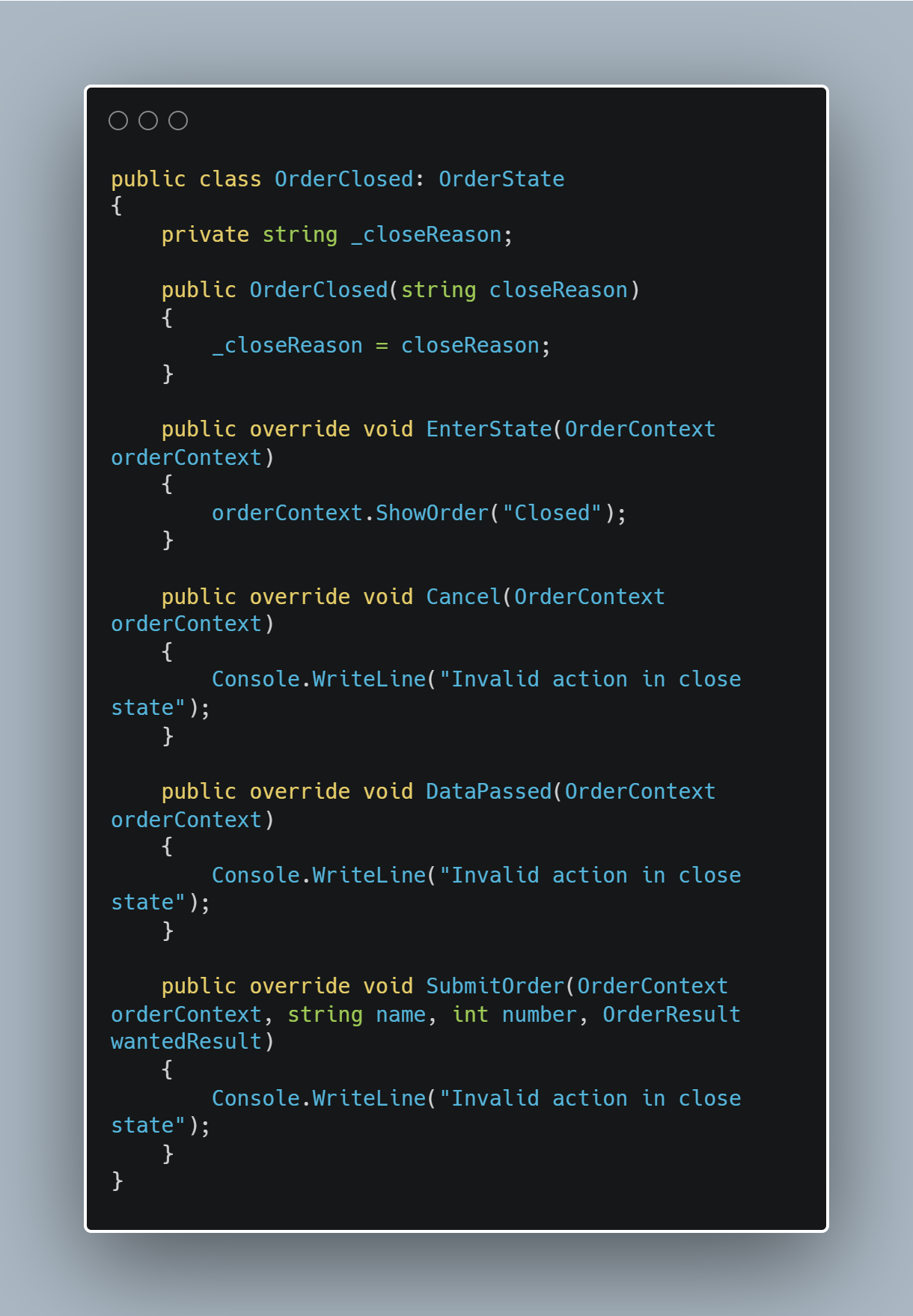

Does it look simpler? I certainly hope so. Yes, we have a little more code, about six times more classes. But they are finally organised properly. Each state is responsible for itself. Plus, it can put itself in a different state. That's sort of the hallmark of this pattern.

The big plus is that there are no ifs. So, the code is super easy to read. The extensibility of the solution is also fine. If we want to add another state, we just add a class and implement its behaviour there. We do not have to read the spaghetti-like if code. This is quite convenient. You have to admit.

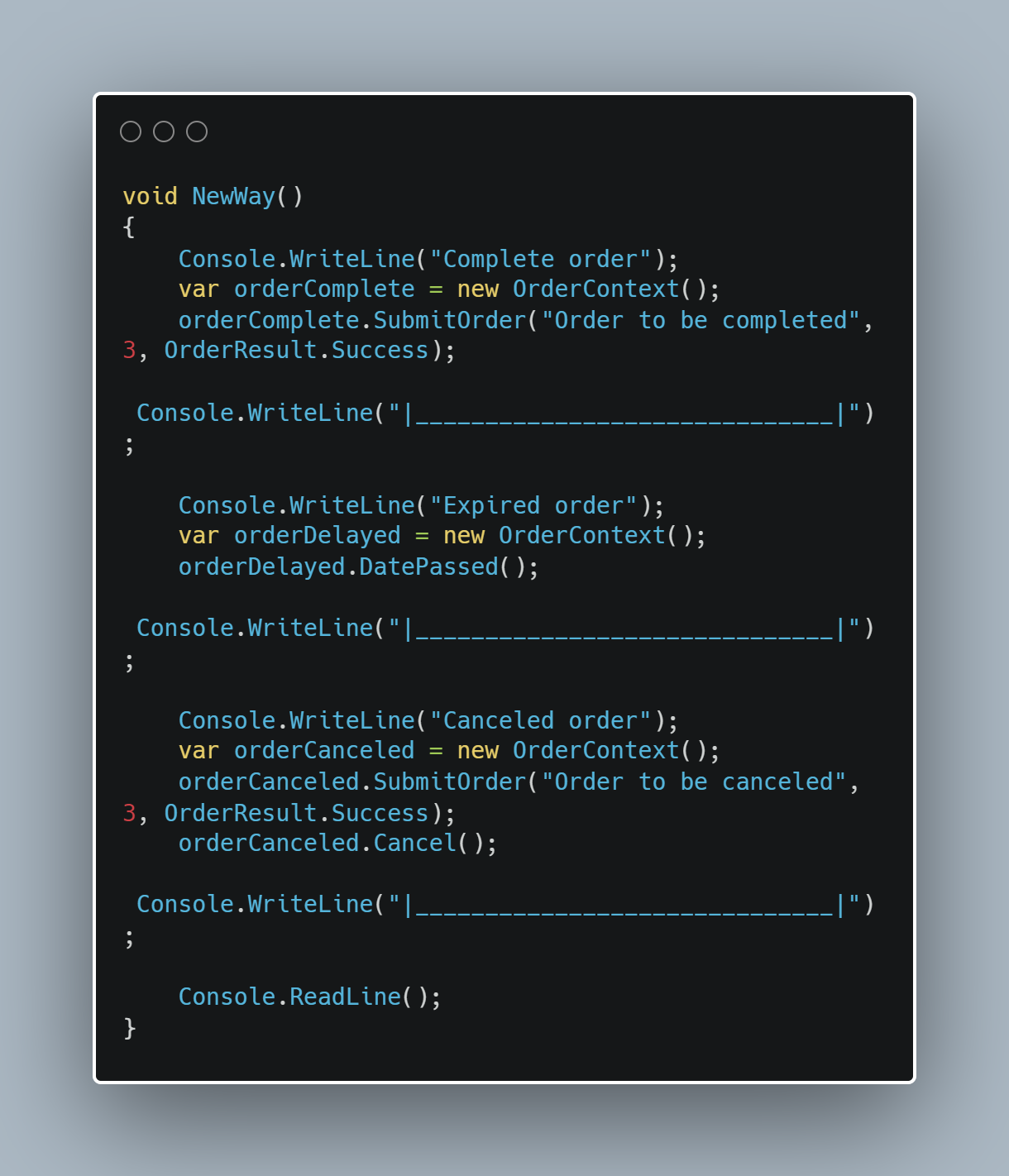

Using the code turns out to be quite simple as well. We are only interested in OrderContext. Once we have an instance of this class, we can call the methods responsible for the order flow. As in a method below.

There are three scenarios. The one where we create and complete an order. The one in which an order expires. And the most complex scenario – when the order is submitted but is cancelled before it can be completed

Summary

The code has undergone quite a revolution. From a huge if infected spaghetti code, we get a code that has no ifs. Please check it out if you do not believe me – it is both well organised, as well as easy to read and maintain. That's a big win in my eyes. And we owe that to well-defined criteria for state patterns and clear definitions of states within the flow.

Like any single pattern, it should be used in cases where value can be gained. Have you used it before? Let me know at karol.rogowski@softwarehut.com.